More than 600 Arkansans died by suicide last year, the highest number over the past decade, and one prevention group is working to get laws in place to help people in rural areas, college students and gay and transgender people, among other groups.

The Arkansas chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, a national nonprofit group that advocates for programs to prevent suicide, will support at least four pieces of legislation in the 2019 session and is working on another measure to improve mental-health care for college students.

The group is still researching and developing details on the language of legislation it would support, said Tyler West, the public-policy chairman for the chapter.

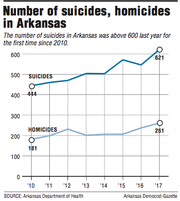

There were 621 suicides in 2017, up from 554 in 2016*. The number of people to die by suicide in the state has risen every year since 2010, according to data from the Arkansas Department of Health.

"It's troubling to see a jump like that," West said Wednesday at a meeting of suicide-prevention advocates across the state.

From 1999 to 2016, every state except Nevada had an increase in deaths by suicide, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The top priority for the foundation's local chapter is finding money to keep open the Arkansas Lifeline Call Center, which answers calls made to the national hotline from Arkansas, West said. The Department of Health operates the center, and anyone experiencing suicidal thoughts or depression can call the hotline at (800) 273-8255.

The center opened at the end of 2017, and has fielded just over 5,000 calls since, according to department data. The center has started using a federal grant, which runs out in September 2019. West said his group hopes to find another grant or a state-level permanent funding sources.

"We'll do what we have to do to make sure that the large amount of money that has been spent establishing this call center doesn't go to waste," he added.

He said a future requirement from the federal government to qualify states for grants makes maintaining the call center especially important.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has mentioned a requirement to be implemented in the future for states to answer 70 percent of the calls coming into the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline or risk being disqualified from future grants, Meg Mirivel, a spokesman with the Department of Health, said in an email.

She added that the department is trying to find money for the call center in case the federal grant, administered through mental health services administration, isn't renewed in 2019.

The next priority is also the most imprecise, West said. The foundation members want to find a way to better serve rural Arkansans, especially farmers.

"When we look at the data of who is dying by suicide, the raw numbers are middle-aged white men," West said. "In Arkansas specifically, the profession that we're seeing trend upwards is the farming and fishing community."

This could be because of lots of time spent alone in those professions, a culture that is not focused on "help-seeking behavior" and a lack of access to care, he said.

There are close to three psychiatrists per 10,000 residents in the state, according to estimates from the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Heather Perry, the project director for the mental-health outreach program at the Arkansas Rural Health Partnership, said her group initiated a mental-health crisis program in May to address needs in the Delta region.

In 2016, slightly more than 1,000 people went to 10 emergency rooms in southeast Arkansas, in the middle of mental-health crises, Perry said. To address that need, the partnership is offering telemedicine programs to 11 hospitals in the region so a social worker can remotely assess patients who arrive during a crisis and refer them to the appropriate follow-up care.

The next steps for the group will be to increase awareness of the need for mental-health services, something West said his group wants to do as well.

"I feel like a lot of individuals still try to kind of sweep it under the rug," Perry said. "It's not really talked about."

West said the foundation is also working with the Trevor Project, a national group that works to prevent suicide among gay and transgender people under 25, to get legislation filed that would ban the practice of conversion therapy in Arkansas.

Conversion therapy is a type of counseling that tries to rid individuals of their attraction to members of the same sex and is controversial.

Nearly every professional mental-health association has denounced the practice or questioned its effectiveness. Studies also have linked it to anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts.

The Trevor Project has started a national campaign to end conversion therapy. Six states have banned it, and there has been legislation proposed in 21 states, according to the project's website.

"We are obviously hopeful that Arkansas will see this as antiquated and outdated and frankly dangerous," West said.

The foundation also is researching so-called red-flag laws, which would allow courts to temporarily confiscate guns from people who are deemed a threat to themselves or others.

Gov. Asa Hutchinson has said that he would be "open" to supporting red-flag legislation, and the issue has gained some attention from legislators, although West said his group was not ready to throw its support behind any particular bills yet.

The final measure the foundation is working on will address mental-health needs on college campuses.

Foundation members are in talks with the Arkansas Department of Higher Education about requiring schools to add the suicide hotline number to the backs of college identification cards, but West isn't sure it would require legislation.

All institutions of higher education are required by Act 1007, passed in 2017, to provide information on mental-health and suicide-prevention services to students. Alisha Lewis, associate director of communications for the department, said the agency doesn't track whether or how schools are complying with the requirement.

"There's a lot of vendors and some options out there about the best ways to communicate this information to college students," Lewis said.

She added that some community colleges and online universities may not have identification cards, but that it would be possible to work directly with certain institutions to get the phone number on the backs of the cards.

The national rate of death by suicide for people ages 15 to 24 was about 13 per 100,000 in 2016, according to data from the prevention foundation.

West said that because college students are going through a transitional time, they need to have readily available information on how to get help.

"Not only are they leaving behind all the support systems and structures that they had depended on, but there's the pressure to be perfect and the pressure to start solving all your problems by yourself," he said.

Information for this article was contributed by Hunter Field and John Moritz of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

A Section on 09/15/2018

*CORRECTION: In 2016, 554 Arkansans died by suicide. An earlier version of this story misidentified the year in which that number of people killed themselves.